Minnesota

How do your programs create public value?

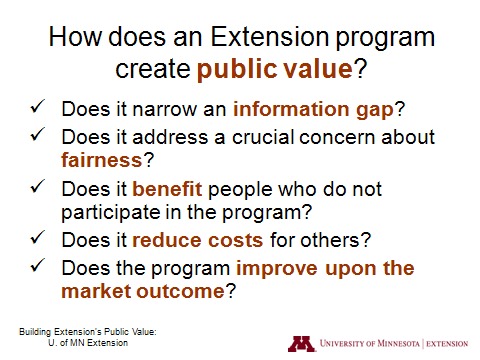

In the Building Extension’s Public Value workshop, we highlight three main ways Extension programs create public value. Programs address concerns about fairness, close an information gap, or encourage actions that benefit the greater community (or equivalently, discourage actions that impose costs on the community). Each of these can be thought of as a criterion or justification for public sector involvement. In my experience, most Extension programs focus on the third type of value creation and base their public value message on the ways a program encourages beneficial activities.

We can’t generalize from this non-scientific poll, but I wondered about the lack of attention to the fairness criterion. In the workshop, I encourage program teams to use this criterion with caution. Whether the unfairness of a situation warrants public sector action is subjective, and stakeholders with different values may assess fairness differently. So, I think Extension makes a more effective case when it uses the fairness criterion selectively. For this reason, I wasn’t surprised by the small number of responses for fairness. I wondered, though, whether it arose because respondents thought their programs did not address a concern about fairness, or if they thought the program did address fairness, but they planned to emphasize a different criterion in order to make a stronger case.

Do you think a relatively small share of Extension programs address a fairness concern? Which criterion would you have chosen for the Extension programs you work with?

The post How do your programs create public value? appeared first on Building Extension's Public Value.

Does public value magnitude matter?

Is it enough for a stakeholder to learn that your program produced public value, or do stakeholders want to know how much value was created? Put another way, is it adequate to demonstrate that a program has a positive return on investment for a community? Or does it have to have a higher return than all the alternative investments the community could have made?

I was asked this question today at a Center for Integrative Leadership Research Forum where I presented, “How Cross Sector Leadership Builds Extension’s Public Value.” It seems that the answer has to be yes, it does matter whether a program generates a large or small amount of public benefit relative to its cost.

A potential funder wants to direct dollars toward their highest use. Ideally, all programs would report a return using a common metric. The metric could be dollars for programs whose impacts can be monetized (i.e., converted to dollars); it could be some other common metric (e.g., amount of pollution remediation, high school graduation rate) for programs addressing similar issues. With common metrics, a funder could rank programs by return on investment and fund as many of the top programs as they can.

Such apples-to-apples comparisons must be rare, though, even for programs with common objectives. I also imagine that the magnitude of a programs’ expected public value–if it is known–will inform, but not drive a funder’s decision.

What has your experience been? Have you sought funding from a source that demands to know the expected return on their investment in terms of dollars or some other metric? Do you know of funders that use those metrics to rank programs by return?

Can public value help you get promoted?

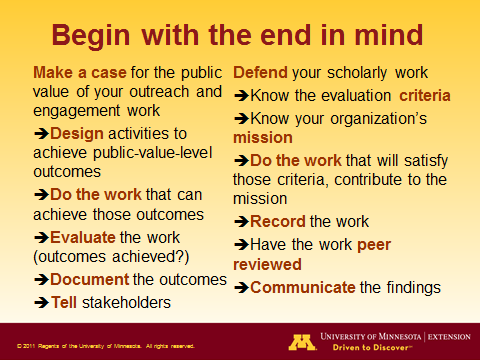

The guidance I came up with is pretty similar to what I wrote about here: begin with the end in mind. Basically, a scholar who aims early on for public value-level impacts and outcomes, and then evaluates and documents those outcomes, will have built a strong case for her work’s public value. Because each step in creating public value involves scholarship–of research, engagement, teaching, and evaluation–the scholar who meticulously documents her contributions should, in the end, be well-positioned to defend her record.

I know, with all of the demands on outreach and engagement faculty, this is easier said than done. I know clients and community-members expect these faculty to engage in activities that are hard to classify as scholarship. But I do think that leading with the end game can help a faculty member prioritize for success.

I also wrote in this blog entry about ways that the public value approach can help close the loop between research and engagement. The research-design-engagement-evaluation loop illustrated in that entry provides a number of opportunities for a scholar focusing on engagement work–in contrast with outreach education–to document her contributions and impact. How did you contribute to (1) the research that underpins the program curriculum, (2) the program design, (3) the engagement itself, (4) the program evaluation? It seems to me that viewing your engagement program in the context of the loop can bring to mind scholarly contributions that you might not have thought to document. Perhaps it can even lead to a more complete promotion and tenure case.

Creating Public Value with Fiscal Policy

Have you studied the scholarship on defining, measuring, and creating public value outside of Cooperative Extension? Wonder how disciplines other than economics define and discuss public value? (Spoiler alert: They don’t all see eye to eye with economists!) Then you may be interested in an upcoming conference sponsored by the Center for Integrative Leadership at the University of Minnesota. The conference, titled Creating Public Value in a Multi-Sector, Shared Power World will be held in Minneapolis September 20-22, 2012.

I wrote one of the foundation papers for the conference on the topic of “Creating Public Value with Tax and Spending Policies.” While not specifically about Extension programs, the definition of public value I use in the paper is the same as that used in the “Building Extension’s Public Value” workshop. We were asked to summarize our papers in five key points, which is a great idea when conference-goers have a lot of papers to digest. Here are the key points from my paper:

1. According to the framework rooted in public sector economics, market failures (such as externalities, information gaps, and public goods) call for cooperative action to make society better off. Which sector should take the action–government, nonprofit, informal–depends on the type of organization that can most cost-effectively address the market failure. Whichever kind of organization acts, effectively addressing market failure can create public value.

2. Governments can create public value by focusing tax and spending policies on (1) achieving economic efficiency by addressing market failure and (2) addressing concerns about fairness embodied in the social welfare function.

3. An optimal tax and transfer policy raises the revenue necessary to fund desired government activities in a way that maximizes social welfare, thus achieving society’s redistributive goals, subject to technological and natural resource constraints.

4. The process through which policies are adopted does not resemble the planner’s problem in social choice theory. Political structures and government’s own failures combine to ensure that real fiscal policies are not the same as the recommendations that arise from the optimal tax literature.

5. Many tools are in place to help the federal and state governments focus tax and spending in ways that can maximize public value, and others are available if we can muster the will to support them.

My favorite lesson from the paper–maybe my favorite lesson from public sector economics in general–is that public value is not exclusively about efficiency, it is also about fairness. Making outcomes more efficient is only the first step. Optimal fiscal policy also addresses society’s concerns about the distribution of well-being among members, also known as fairness.

One more preview for the conference: UM Extension Leadership and Civic Engagement Educator Lisa Hinz and I are working on another paper for the conference on “Using Economic Principles to Show How Extension Education Programs Create Public Value.” I’ll share the abstract of that paper when it is ready, so stay tuned!

Discussing public value from youth programs

There has been a lively discussion about communicating the public value of youth development programs on “Youth Development Insight,” a blog of the University of Minnesota Extension Center for Youth Development. Community program specialist, Joanna Tzenis argues that youth programs can create public value by having society-level impacts. Examples of two such impacts are building trust among community members and youth becoming agents for change in their communities. You can check out the discussion here.

The late-workshop slump

I got some constructive feedback on a recent four-hour “Building Extension’s Public Value” workshop that I taught here at the University of Minnesota for NELD. While the evaluations were largely positive, I also heard that some participants grew weary toward the end of the workshop and even “checked out” during the later small group exercises. One participant wrote on the evaluation form, “Content was very good, but a very long time sitting with no activity.”

This lead me to search for activities I might include in the second half of the workshop–which often occurs in the sleepy after-lunch hours–that would get people up out of their seats and moving around. I admit that I am torn, because even without adding new activities, it is hard to achieve all of an organization’s workshop goals in the allocated time. So, I do not want to add anything to the workshop that doesn’t advance the BEPV learning objectives.My search brought me to the University of Minnesota’s Techniques in Learning and Teaching (TILT) blog. The October 17, 2011, entry is about reinvigorating student learning during the “mid-term slump.” My issue is more with a “late-workshop slump,” but I’m willing to try some of the suggested techniques. For example, I think I can adapt the flipchart-page-synthesizing technique to the BEPV workshop. It is described here:

“Version 2: Create four flip chart pages, each with its own unique synthesizing question and post each page at different locations around the room. Group students in 3s or 4s and have them discuss the question on one chart, come to a consensus, and then record their thoughts. At a designated time all groups rotate to a new flip chart, review and respond to previous groups and raise new questions. By focusing the four questions on a specific, common-to-all case or scenario, students must draw on all they have studied to analyze and address the discrete components of an overall problem, while also reflecting on how content and coherence of previous commenters.”

I can think of two ways this technique might work:

(1) I could use the activity to help participants synthesize the main content of the BEPV workshop (modules 1-4): the criteria for public sector action. I’m not yet sure what the “unique synthesizing questions” for the flipchart pages would be…perhaps something like, “Can the criteria for public sector involvement be used to justify public funding for any Extension program?” Alternatively, each flipchart page could simply hold one of the criteria, as identified in the slide below, and groups would add to each page examples of Extension programs that satisfy the criterion.

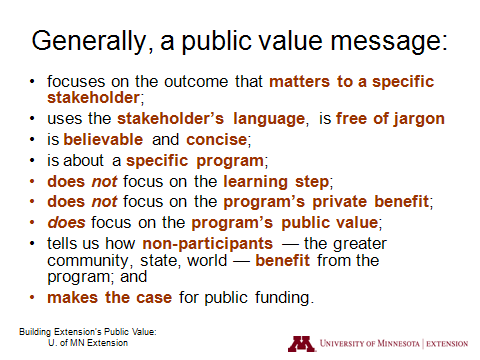

(2) After participants complete the “Demonstrating Extension’s Public Value” activity (module 8), but before they refine their work with the public value message template (module 8.1), I could post draft public value messages on four flipchart pages. The messages would come from elsewhere, i.e., not from the workshop participants. I would sort participants into new small groups, as explained in the TILT blog excerpt, and ask each small group to critique the draft messages. Perhaps they could re-draft the messages on the flipchart pages. If there is enough time, I could rotate the small groups through the flipchart pages, asking them to improve upon the previous groups’ work, if possible. The slide below, providing some guidelines for drafting messages, could serve as a resource for the activity.

What are your reactions to these ideas? Is it worthwhile trying to invigorate the second half of the workshop with a get-up-and-move-around activity? Do you think the suggested activities would help accomplish the learning objectives, and not simply add minutes onto a tight agenda?

Constructing a public value message in real time

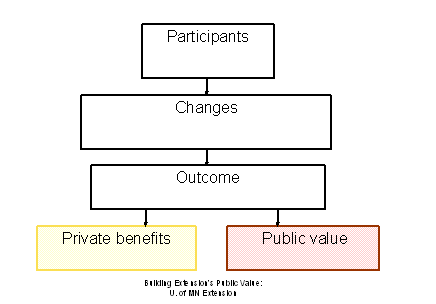

We included a blank version of the public value message graphic, like the one below, except with empty boxes. Prior to the session, we asked Sue Letourneau, program leader for health and nutrition programs, to share a public value message for Extension’s Simply Good Eating program. I created a slide that included Sue’s text within the message graphic and added animation that brought the text in one box at a time. At the session, I asked Sue to present her message, explaining how her team arrived at the language they chose.

Given the short amount of time, we hope this approach helped participants see how a program team can go about constructing a public value message, even if they didn’t get a chance to do so themselves. It also gave an example of a UM Extension program that had completed the workshop, hopefully dispelling concerns that it would be too demanding. Finally, Sue helped participants see how the public value message was related to the research agenda that the Simply Good Eating program team is currently implementing.

It’s all in the timing

That varied set of experiences, together with recent conversations with Extension staff who are gearing up to teach workshops in their own states (shout out to New York and Georgia!), made me think that we could benefit from an exchange of ideas about timing.

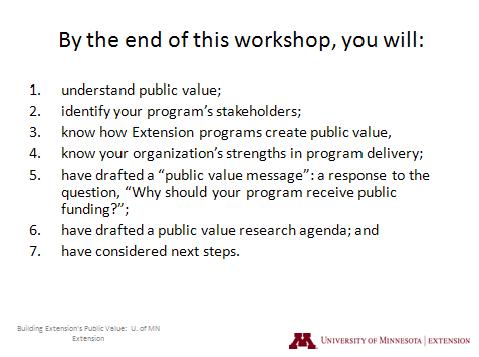

I have experimented with a number of different structures for the BEPV workshop, but the most common takes about four hours, including a couple of short breaks. Of course, in that amount of time, I can’t teach all of the modules in the BEPV Presenter’s Guide. But, we can usually complete the content and activities for the modules shown below:

Note that the last goal is “have considered next steps,” and not “have completed a public value action plan.” A four hour workshop may not give us enough time to complete the action plan module. Depending on the audience’s objectives, I sometimes replace the full module with a large group discussion about next steps.

As I teach in the BEPV Train-the-Trainer course, I use caution when I skip workshop modules. Each of the optional modules was added to the curriculum, because I repeatedly fielded questions on that topic. So, when I skip a module and the associated exercise, I spend at least a few minutes talking about the issue that the module is intended to address. For example, if I don’t cover module 9, “Maximizing Public Value,” I lead a short discussion about the different types of program characteristics that are responsible for public value outcomes.

If you have taught a BEPV workshop, how much total time did you use? What were you able to cover in that amount of time? If you’ve participated in a workshop, how long was it? Did it seem like the right amount of time? Rushed? Did it drag on? Would you preferred a different schedule?

The unreachable stakeholder?

Last week I presented a mini public value workshop as part of University of Minnesota Extension’s Fall Program Conference. When I suggested that public value messages should address the specific concerns of individual stakeholders, a question came up that I have heard several times before. Are there some stakeholders who will never be receptive to our messages about public funding for Extension programs? No matter how hard we try, are some stakeholders simply unreachable?

I think that particularly skeptical stakeholders pose a challenge, to which we must try to rise. After all, we wouldn’t have identified them as stakeholders if their support for Extension weren’t important. Conversely, if all of our stakeholders were easy for us to reach, Extension would already be enjoying long-term financial sustainability.

Here are my suggestions:

==Consult with others in the organization who may have a better idea than we do of what matters the most to the challenging stakeholders. External and legislative affairs professionals, regional Extension directors, Extension liaisons to stakeholder groups in your state come to mind.

==Find stakeholders who are sympathetic to Extension, but who are otherwise similarly situated to the challenging stakeholder. For example, do you know of a “friend of Extension” who is in the same line of work, of the same age, living in the same region? Ask that person how they came to understand the value of Extension in their community and what information helped them choose to support Extension.

==If the stakeholder is a public official, study what she has said and written–not only about Extension, but about a variety of topics–to get an idea of what really matters to her.

==Evaluate whether this stakeholder truly is crucial to your program, or if it would not be a great loss to focus your efforts elsewhere.

What do you think? What kinds of stakeholders seem to be unreachable? Have you had success with them? What has worked for you?