While the objective of the “Building Extension’s Public Value” workshop is to draft a qualitative message about a program’s public value, many of our stakeholders are concerned about programs’ financial impacts. For example, county commissioners and state legislators want to know how much a program will cost, and whether it’s impacts will reduce strain on the county or state budget. A lot of us, therefore, are eager to quantify the impacts of Extension programs and, wherever possible, convert those impacts into dollars and cents.

Some exciting work is being done on monetizing Extension program impacts. These economic impact briefs from Texas AgriLife Extension are a strong example, and I know there are many more studies.

In future blog entries, I’ll write more about ways researchers and program evaluators are quantifying and monetizing Extension program impacts. However, as persuasive as a dollars-and-cents case can be with some stakeholders, I can think of two reasons to proceed with caution as we pursue more financial and fiscal impact studies.

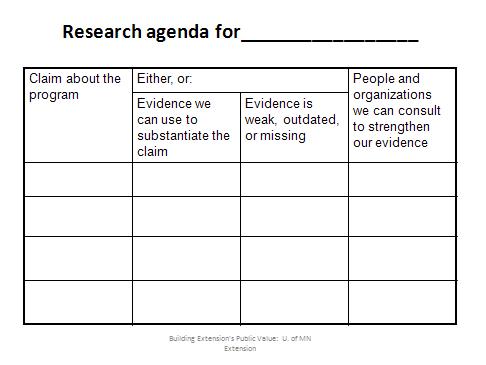

First, Cooperative Extension does not yet have all the resources and tools necessary to estimate the financial and fiscal benefits of all of our programs. To do a credible job, applied economists, program evaluators and others would need to devote many more hours to this effort than are currently available. Data must be collected and analyzed, models built and tested, reports written and vetted. The likely result of pressuring program teams to estimate financial impacts while providing them with inadequate resources is a collection of poor quality analyses that erode Extension’s credibility.

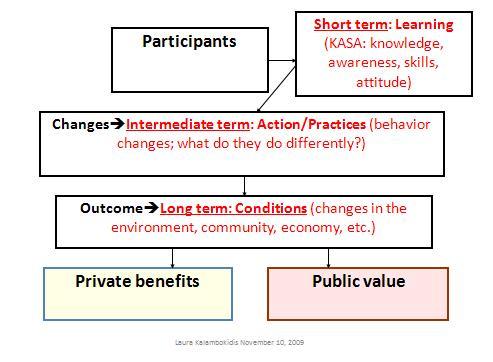

Second, some programs’ public value lends itself more readily to monetization than others. For example, a program that helps reduce a county’s cost of managing its waste can make a strong, straightforward, dollars-and-cents case. On the other hand, methodologies for estimating the fiscal impact of social capital improvements are less well-developed.

Because so many of Extension’s stakeholders are concerned about monetary value, I am concerned that those programs whose public value is more easily monetized will rise to the top of the priority list–not because they contribute more public value, but because their value is easier to translate into currency.

The objective of the BEPV workshop is to make strong qualitative cases for all Extension programs that create public value. I hope we can keep doing this, even while we seek the resources necessary to estimate the financial and fiscal impacts of those programs for which that is possible.