Logically speaking about public value

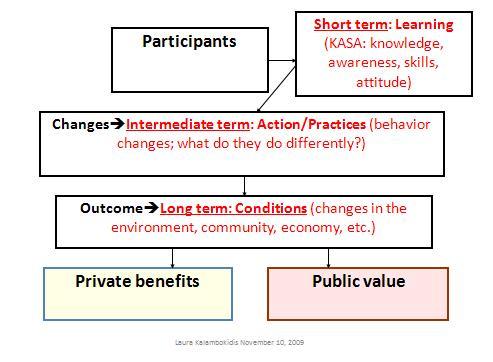

Many of you use the University of Wisconsin Extension logic model to guide program development and evaluation. Below is my first attempt at mapping the elements of the logic model to a public value message.

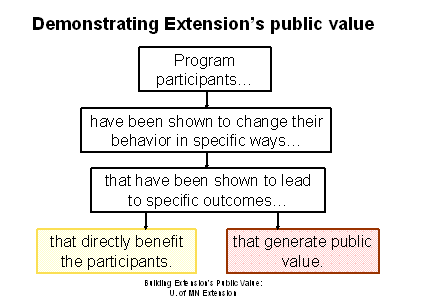

The “short-term” or “learning outcomes” in the logic model are a means to achieving the behavior changes and outcomes contained in the public value message. These learning outcomes lead the way to public value–and we must identify and measure them–but they are not the focus of the public value message. A skeptical stakeholder is unlikely to be persuaded of a program’s value be hearing that a participant learned or became aware of something. The stakeholder is concerned with what the participant actually did with that knowledge.

What I call “changes” in the public value message are called “intermediate” or “medium term outcomes” in the logic model. What I call “outcomes” are the logic model’s “long-term outcomes” or changes in conditions.

It seems to me that public value typically arises from a program’s long-term outcomes. In some cases, a program’s logic model will already include the outcomes that a stakeholder cares about (public value). In other cases, the public value exercise will tell us which additional outcomes we need to monitor–how we should extend the logic model–in order to substantiate our public value messages.

I believe that the public value approach must work hand in hand with program evaluation: it is through good program evaluation that we are able to make credible statements about our programs’ public value.