Last week I spoke at Purdue University’s Scholarship of Engagement Workshop: Making the Case for Promotion. The workshop was a resource for Purdue faculty who devote significant effort to public engagement and need to document the impact of that work for their promotion and tenure cases. My talk was about “Creating Public Value with Scholarship and Engagement,” and I’ll tell you more about what I presented in a future blog entry.

The existence of a workshop like Purdue’s testifies to the emphasis that land grant universities have placed on the “engagement” activities of their faculty and students. Many are striving to be “engaged universities” and to promote the “scholarship of engagement.” As someone who works with Cooperative Extension, I wonder about the relationship between Cooperative Extension and “public engagement” as universities now define it. In particular, it seems that land grant universities that want to become more engaged need only look to their own Extension organizations, which have been practicing public engagement since the Smith-Lever Act was signed.

So, what do land-grant universities mean by “public engagement” and does it encompass Extension? (I added the emphasis in the quotes below.)

The University of Minnesota’s Office of Public Engagement says:

“Engagement is defined as the partnership of university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good.”

From the University of Illinois’ Office of Public Engagement:

“As a land grant institution the University of Illinois has a long record of commitment to public engagement and to the discovery and application of knowledge to improve and serve the greater society in which we live. Its faculty, staff and students collaborate with external audiences and partners to address the needs and opportunities of society. It is through these partnerships that critical societal issues are embedded into and impact the research and educational missions of the University.”

Purdue University’s Office of Engagement says:

“Purdue believes in being a good neighbor. Through the Office of Engagement, the university uses its resources to address issues affecting the state’s prosperity and quality of life.”

Imagining America, whose Project Director for Research and Policy, Tim Eatman, also spoke at the Purdue workshop, explains university engagement this way:

“Our activities are based on the conviction that making universities more civic requires ongoing collaboration with partners in the public and non-profit arenas.”

Finally, many public university offices of engagement are modeled after recommendations in the The Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities’ third report, “Returning to Our Roots: the Engaged Institution”:

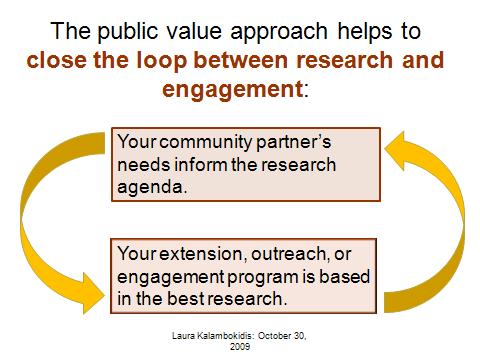

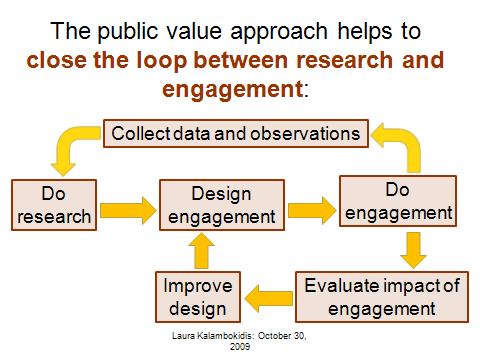

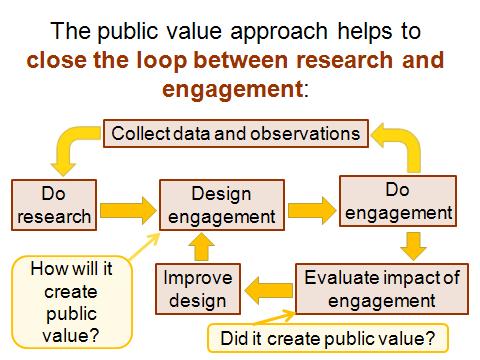

“This Commission defines engagement as something that goes well beyond Cooperative Extension and conventional outreach. It even goes beyond most conceptions of public service. Our inherited ideas emphasize a one-way process of transferring knowledge and technology from the university (as the source of expertise) to its key constituents. The engagement ideal is profoundly different; embedded in it is a commitment to sharing and reciprocity. By engagement the Commission envisioned partnerships, two-way streets defined by mutual respect among the partners for what each brings to the table.”

Within these definitions, I see two primary objectives for engaged scholars: (1) apply knowledge and expertise to address community needs and promote the public good and (2) work toward this end in partnership with constituencies outside the university. As Tim Eatman said at the Purdue workshop, “engaged scholars are co-creators with their community partners.”

While the Kellogg Commission argues that public engagement “goes well beyond Cooperative Extension,” it seems to me that contemporary Cooperative Extension–at its best–now goes well beyond traditional, one-way, outreach. By the definitions of the universities themselves, Extension is an example (exemplar??) of public engagement. Is Extension’s work viewed this way at your institution? Do you see instances where Extension falls short of the engagement ideal?

(Incidentally, until I started fishing around the Internet, I did not know there was a Journal of Community Engagement Scholarship. Did you?)