Private benefits from short-term outcomes

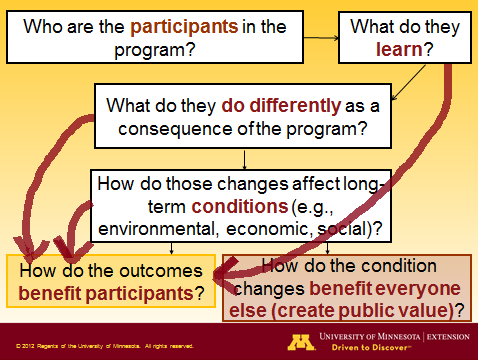

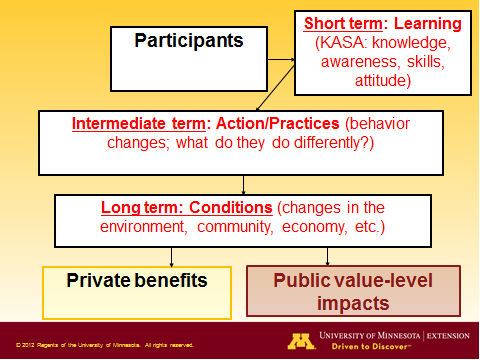

The students in my recent lecture for the Penn State University Agricultural Extension and Education program asked me several useful questions. One was whether the public value message structure (below) implied that private benefits can only be accrued after condition changes have occurred. Note that the thin, black arrow leading to the participant’s private benefits implies exactly this.

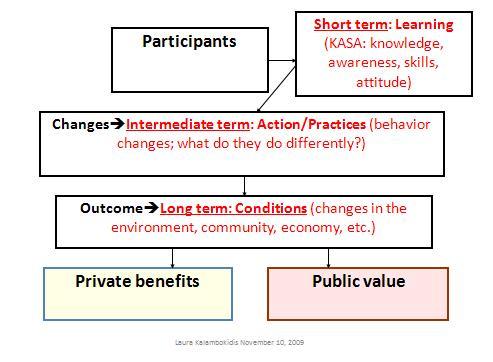

In fact, I think the original construction–with the arrow extending from condition changes to private benefits–misleads. A program participant may very well enjoy benefits long before conditions have improved. Indeed, many participants directly benefit from improvements in knowledge and skills. For example, a participant in leadership development program may see personal career benefits from the enhanced leadership and facilitation abilities he acquired through the program. And this may occur well before the program can claim improvements in community conditions. So, I wonder if the diagram should be redrawn (as I did above) to indicate that those private benefits can, indeed, arise from the intermediate stages in public value creation. What do you think (besides that I need to employ someone with better graphic design skills than mine. :))?