Does public value magnitude matter?

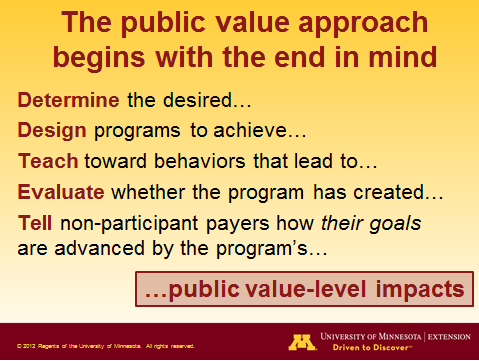

Is it enough for a stakeholder to learn that your program produced public value, or do stakeholders want to know how much value was created? Put another way, is it adequate to demonstrate that a program has a positive return on investment for a community? Or does it have to have a higher return than all the alternative investments the community could have made?

I was asked this question today at a Center for Integrative Leadership Research Forum where I presented, “How Cross Sector Leadership Builds Extension’s Public Value.” It seems that the answer has to be yes, it does matter whether a program generates a large or small amount of public benefit relative to its cost.

A potential funder wants to direct dollars toward their highest use. Ideally, all programs would report a return using a common metric. The metric could be dollars for programs whose impacts can be monetized (i.e., converted to dollars); it could be some other common metric (e.g., amount of pollution remediation, high school graduation rate) for programs addressing similar issues. With common metrics, a funder could rank programs by return on investment and fund as many of the top programs as they can.

Such apples-to-apples comparisons must be rare, though, even for programs with common objectives. I also imagine that the magnitude of a programs’ expected public value–if it is known–will inform, but not drive a funder’s decision.

What has your experience been? Have you sought funding from a source that demands to know the expected return on their investment in terms of dollars or some other metric? Do you know of funders that use those metrics to rank programs by return?